This week I’m writing about the child care crisis, taking each day to discuss a different aspect of child care as a public policy. Today: an explanation of the crisis.

Something Bad is Coming

What’s Different About Child Care

The Millions at Stake

Forever Problems

1. Something Bad is Coming

On September 30th, America will amble—much like a toddler taking their unsteady, swaying first steps—right off a childcare cliff. The American Rescue Plan Act signed by newly inaugurated President Biden at the start of 2021 infused billions into the fledgling child care industry via grants to state governments. By the end of 2022, that money had:

reached 220,000 providers, more than 80% of the total in the US,

who look after 9.6 million children,

helped center-based providers pay for personnel costs (average aid was $140k)

helped home-based providers pay for rent and utilities (average aid was $23k)

in every state in the U.S.

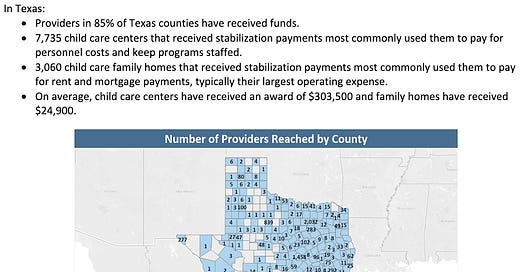

How many in your state and county? You can see here. For example, my home state of Texas got $2.7 billion in the first two years of fund allocation. Their centers received grants about twice as large as the national average ($303k versus $140k).

On September 30th, these grants expire and no more money is coming. It was a historic infusion of cash to an industry desperately in need of it. It’s never been supported so much, which means it has never had this much help taken away. We don’t know what will happen, but it won’t be good.

2. What’s Different About Child Care

A lot of industries got help during the pandemic. Airlines, for example, got over $50 billion through numerous acts, mostly to cover payroll costs. And the aid makes sense. The airline industry has a viable business model and stable market. The pandemic put a terrible strain on that. The government eased the strain with cash in lieu of market revenue so that once the pandemic ended, the airline industry would be (mostly) right where we left it and back to functioning, business as usual.

Child care isn’t like that. It’s a market failure and has been for some time. It doesn’t have a viable business model or a stable market, but high prices and unmet demand. The government intervention into child care during the pandemic was not, like airlines, temporarily propping up an industry that had a revenue hit, but instead subsidizing a failing business model.

The average cost of childcare in the US is $10,000 per year, but in many localities it’s $15,000-$20,000. A family with two kids in care would spend more on child care than they do housing, college tuition, transportation, food, or health care (*except that in the West Region, where housing is just above care).

Care.com researchers have reported that on average families report that a fourth of their income goes to child care. Over the past ten years, the cost of infant care has nearly doubled.

The pandemic and the federal intervention did nothing to change the fundamentals of the child care industry. It is still failing. And we are about to stop subsidizing.

So what happens when the spigot of federal money that has been flowing for nearly three years turns off?

3. The Millions at Stake

The best projection of what the impact of the child care cliff (the nickname for the September 30th cutoff) comes from The Century Foundation.

They estimate that 70,000 providers will shut their doors and close, and 3.2 million children will lose their spot as a result. This wave will not be evenly distributed throughout the country, the states who could lose up to half their providers are: Arkansas, Montana, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington D.C. Another 14 states could lose a third of providers.

Will this actually happen?

Right now the federal government is giving money to states to allocate to providers. When the federal money turns off, it’s possible that states will try to make up the difference and mitigate the loss.

Not every provider will have to close, but most will have to do something to make it work without the help. The likely response would be to raise prices, and in a survey of care providers, 43% of them said they would immediately raise tuition. There’s no estimate of the effects of this in the “x million children lose spots” because the spots themselves wouldn’t be gone, it would just be some millions who could no longer afford them.

The market would likely work itself out so that—whoever loses a spot or sees a price increase initially—the new equilibrium would be for richer parents to have children in the remaining spots at higher prices.

4. Forever Problems

The childcare market has what I think of in terms of market economics as “forever problems.”

Problem 1: Unresponsive to strength. It doesn’t matter how strong the economy is, there’s no point where all we need are some market conditions met and then—boom!— child care is fixed. It will always be a problem. Put differently: There is no economic recovery coming for the child care industry.

Problem 2: Unresponsive to scale. There’s only so many children you can safely watch at one time.

Problem 3: Unresponsive to innovation. There’s no innovation coming that can change the fundamentals: children need constant attention so, at a minimum, they don’t severely harm themselves or, here’s hoping, they learn and grow. How we look after children has not changed much for the past couple of thousand years or so and won’t change much in the future. It’s an eyes-on, hands-on activity.

These are permanent aspects of childcare: can’t ride market coattails, can’t scale, can’t innovate. It begs the question, what does the government expect to happen when the federal aid ends?

This week I’ll write more about what we lose when we lose child care.